In our first week in China we explored all of Shanghai’s major sights and attractions in oppressive heat, covered many more miles seeing Suzhou’s gardens and canals, and ascended around 7,000 steps (and 5,000+ feet) to the top of China’s holiest mountain, Taishan. Needless to say, by the time we reached Beijing, we were dog tired. We spent four nights in China’s capital, which ended up being a fairly relaxing city compared with the likes of frantic Shanghai. We saw very little of Beijing’s big sights which allowed us to recharge our batteries for the remaining three weeks in China.

Beijing turned out to be a great place to lay low for a few days. The ever-present “fog” kept temperatures much lower than previous places we had visited, and the occasional drizzle was a welcome change. Of course, we had no idea that in another 10 days the entire city would be submerged by massive widespread flooding (though the floor of our hostel room did flood one evening due to heavy rain), so we feel quite fortunate to have visited when we did.

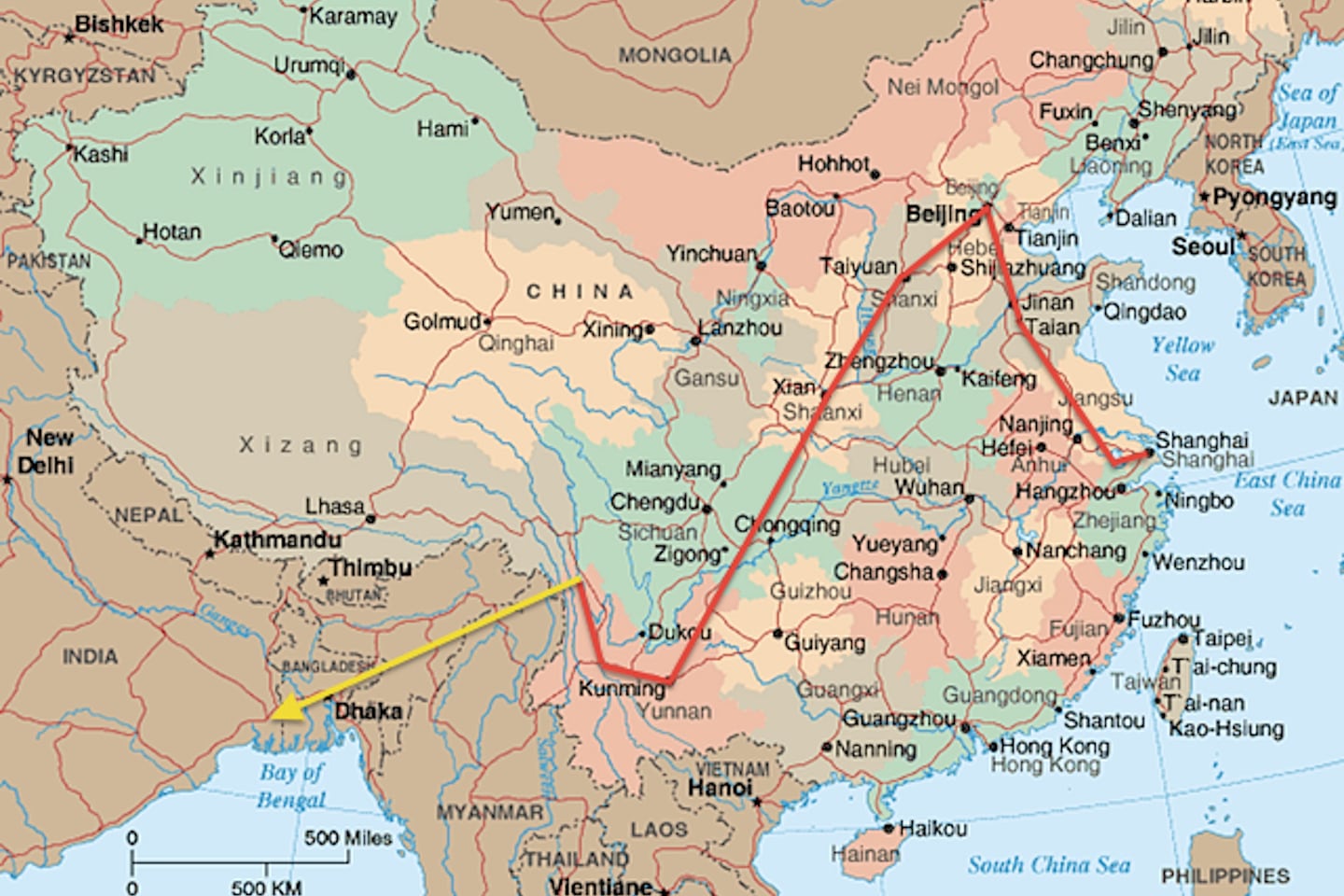

Speaking of rain, it may not come as a surprise to hear that China’s gotten much more than its fair this summer. We originally had intended on leaving Beijing, heading to Pingyao, then on to Xi’an to see the Terracotta Warriors, taking an overnight train to Chongqing (via Chengdu to see the pandas), the start of a three-day Yangtze River boat cruise, before heading down to Yunnan Province. As is often the case with international travel (which makes it so appealing to Lori and I, albeit incredibly frustrating at times) is that things rarely go the way you plan. As I’ve mentioned in previous posts, China’s long-distance trains can be impossible to book in the summer months unless you plan ahead. Long runs down to Chengdu and Chongqing are extremely popular these days and book up weeks in advance. A little known fact for foreigners is that ticket sales open to Chinese tourists long before they open to foreigners, and unlike India, there is no foreign tourist quota, so foreigners are really at a disadvantage in terms of train bookings.

For all our efforts, we could not find a reasonable way to get from Xi’an down to Kunming (Yunnan Province) via Chengdu and Chongqing, at least nothing within a week of when we wanted to travel. So, in the end, we made the tough decision to pony up for a flight from Xi’an to Kunming (which actually ended up comparable in cost to the soft-sleeper berths we would have booked). This meant we would have to forgo our Yangtze River cruise for the time-being but also freed up an additional week to distribute among our remaining destinations (reducing the frenetic pace that we had set for ourselves).

It turned out the decision was the right one for us. Not only were we able to add some breathing space into our travels, we later learned that Sichuan province and the Yangtze River had experienced extreme flooding during the times we would have visited, killing dozens (not to mention disrupting travel plans for thousands). It would have been an absolute mess. Instead, we were relaxing under sunny skies in beautiful Pingyao with plans to hop over the remaining bad weather on a plane.

While in Beijing, however, we did get out a bit to see some of the city’s most famous sights including Tiananmen Square and the Forbidden City, Jingshan Park, and the 2008 Olympic Games complex. We also explored Beijing’s hutong alleyways, and the Great Wall, the subject of a future post.

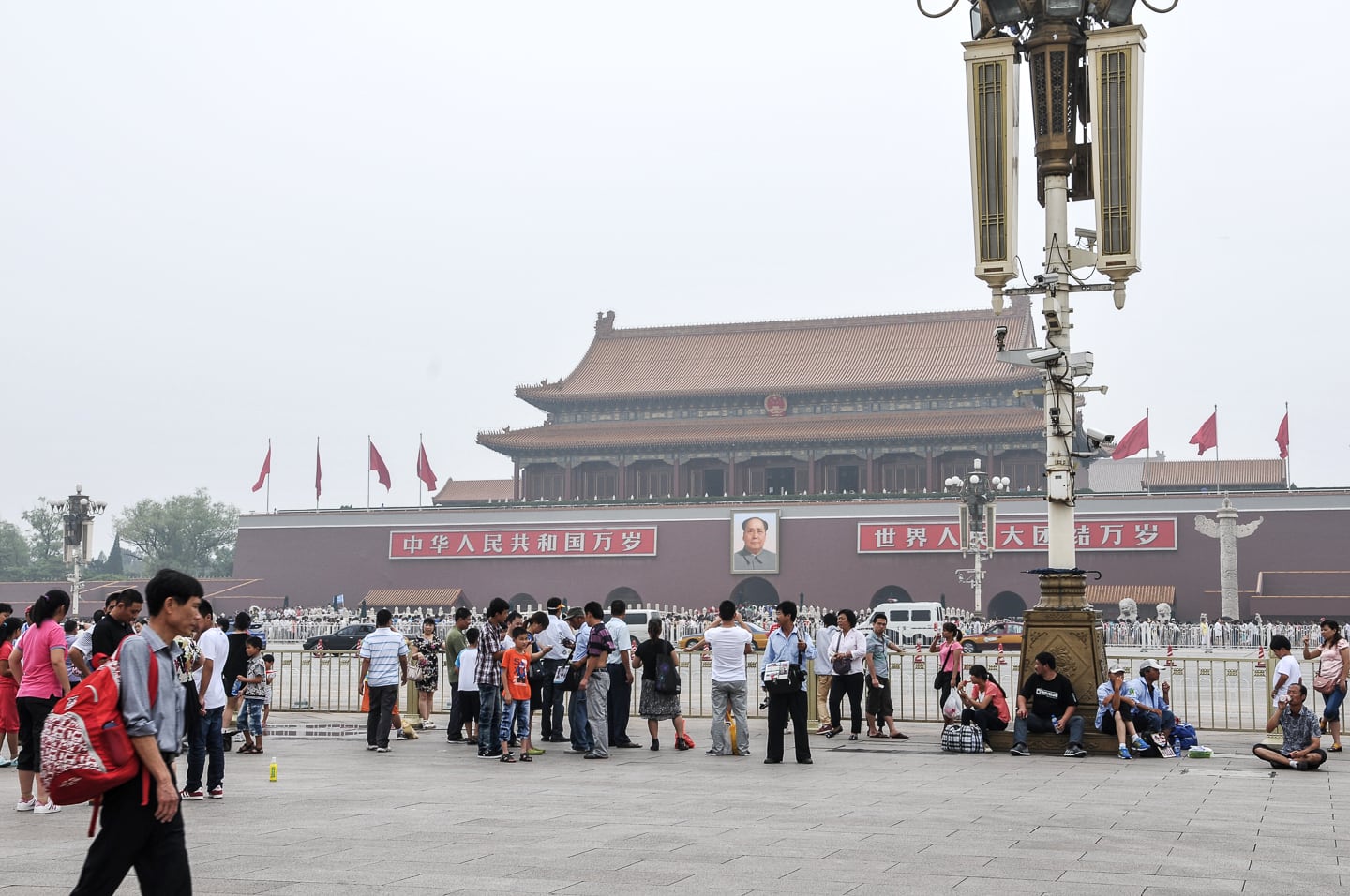

Tiananmen Square

Tiananmen Square is a strange place – a massive concrete space (the third largest public square in the world) measuring 109 acres, or 5.5 football fields wide by 10 football fields long! It is certainly like no public square I’ve ever been to, and for all of Chinese practicality and ingenuity, the square is the largest, most impractical waste of public space I’ve ever laid eyes on. What exactly do the people of China do in their people’s square? That’s an excellent question. For in this public place there is no shade from the summer heat, and not one single, solitary bench, pillar or stump to sit on. What there are a lot of are security cameras and uniformed guards (and many more plain clothes guards, or so I’m told). The square is extremely austere, gray, dismal and monotonous, surrounded by enormous and uninviting Maoist government buildings. The center piece of the square, of course, is the final resting place of Mao Zedong. His body is actually there for public viewing, if you’re so inclined.

If we had landed in China on Tiananmen Square (undoubtedly long enough for a small jetliner), I don’t believe Tiananmen would have stricken me as all that strange. Tiananmen, afterall, embodies what many Westerners are accustomed to thinking of when we think of China. It’s an image cultivated in literature, media and the imaginations of Americans especially — Uninviting Communist architecture, machine-clad uniformed guards and soldiers high-stepping in perfect unison, Red Chinese flags at every interval and enormous paintings of Mao draped over every building in site.

After several weeks traveling through China I can say with much confidence that if the image I described was ever a far-flung reality in China, it is no longer, but in the confines of Tiananmen Square. The reality of modern-day China is that it is not a Communist police state, at least not in ways that can be immediately felt and seen on the surface and in everyday interaction with people. The average Chinese seems far too content to concern themselves with family, wealth and personal matters than public issues, and shies away from anything which threatens to upset the harmony of their own lives.

Point in fact: A collision between two vehicles or abusive husband dragging his wife kicking and screaming across a busy railway station waiting room — If uniformed police are present and visible they will very likely do nothing to intervene, nor will onlookers, lest their interference upset the harmony of things (The harmonious society is afterall the grand goal of PRC society). In this respect we felt both the most and least safe we’ve felt anywhere in the world — the most because violent crime (especially towards foreigners) is virtually unheard of and the penalties for such are extreme — and the least simply because we were absolutely convinced that if something did happen to us in broad daylight on a busy street, no matter how appalling by any standard, no bystander nor security official would intervene on our behalf. It was a sobering notion, but this sort of unwritten social agreement doubtless works in favor of the American tourist while against the individual Chinese who wishes to stand up and speak out against injustices, state censorship or other human rights issues.

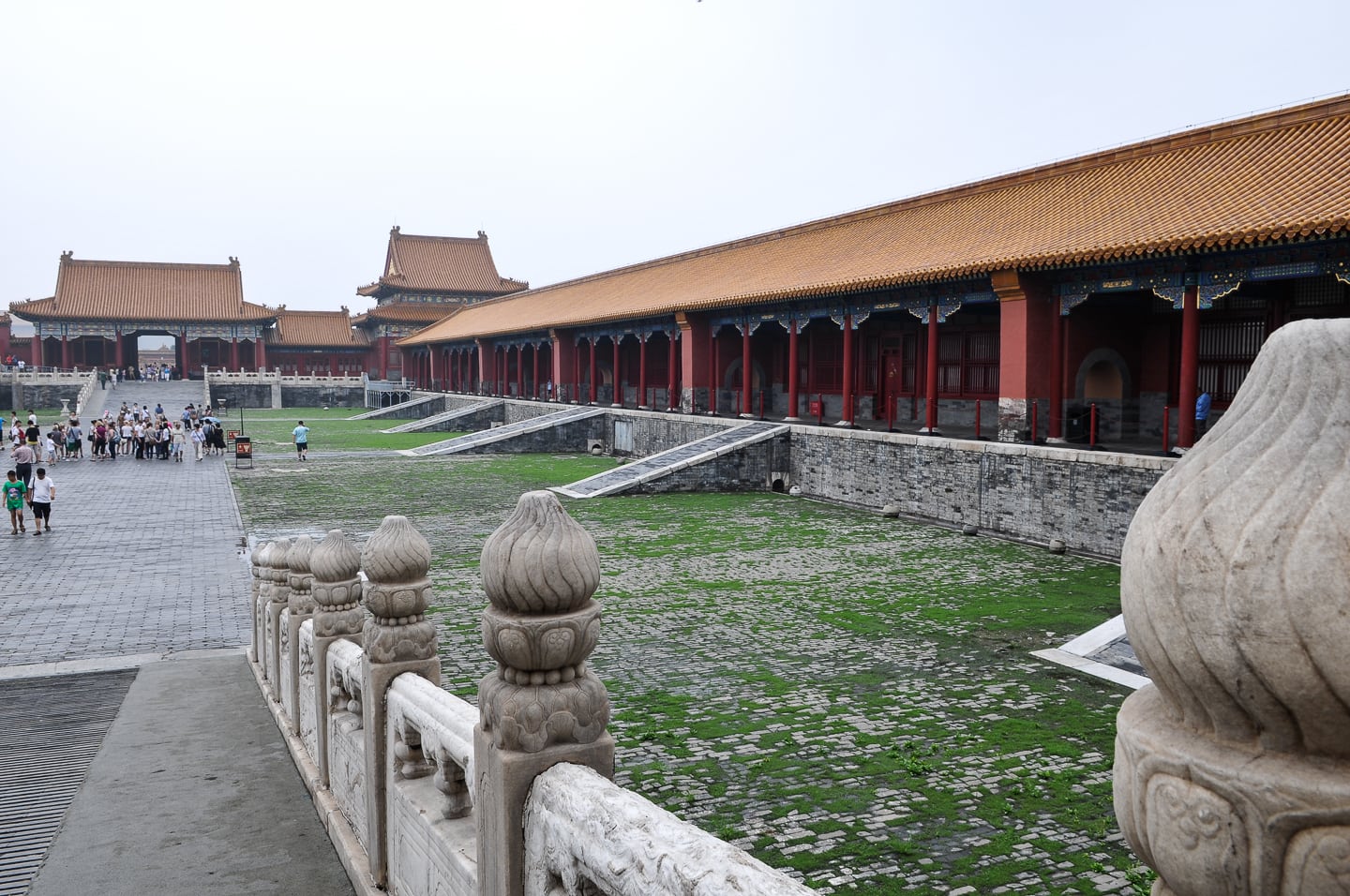

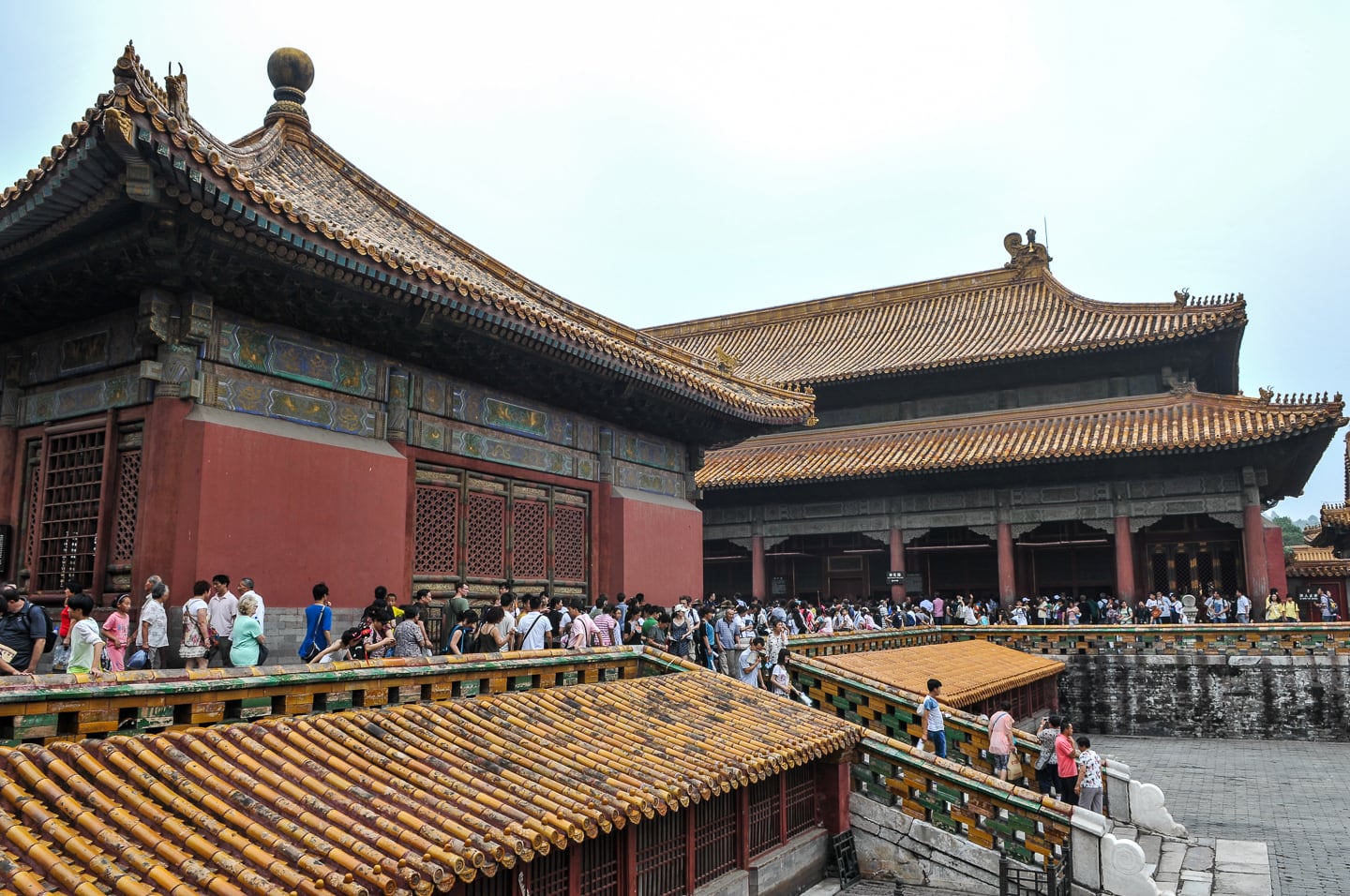

The Forbidden City

The Forbidden City (commonly referred to as the Palace Museum) is a mind-blowingly large Ming/Qing Dynasty palace encompassing dozens of courtyards, halls and pavilions. Only a fraction of the entire city is open to the public, but those parts are more than enough to satisfy the average person’s curiosity and interest. The Chinese certainly have a penchant for presentation and suspense which plays out in spectacular fashion here. Perhaps the most notable aspect of the complex is that each gate (and there are many) open into an even larger, even more impressive courtyard than the last, and this continues, and continues.

As with so many major international sights in China, we were surprised to find very, very few non-Asian tourists touring the complex. This was especially surprising in the Forbidden City given that everyone who comes back to the U.S. from a visit to China most certainly visits the Forbidden City. Yet, where are all of those Western tourists? Eclipsed by the sheer number of Chinese and other east Asian tourists of course. This shouldn’t seem surprising to us, but it is, for this is not at all the case at Machu Picchu, the Colosseum of Rome or even the great sights of London, where foreigners outnumber locals a dozen to one or greater. Only in the United States’ own National Parks have we experienced anything like this, if on the other end of things.

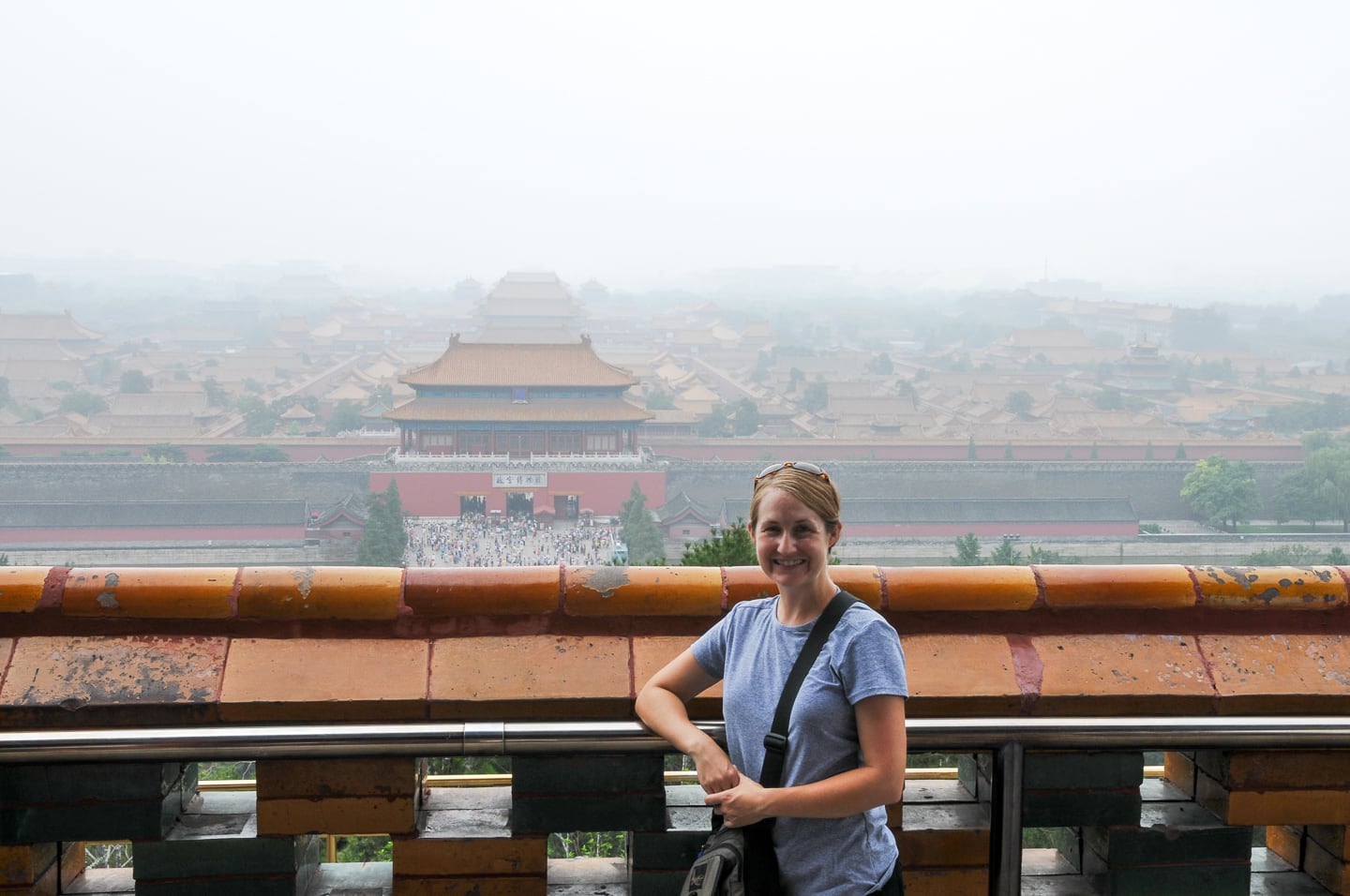

Jingshan (West Gate) Park

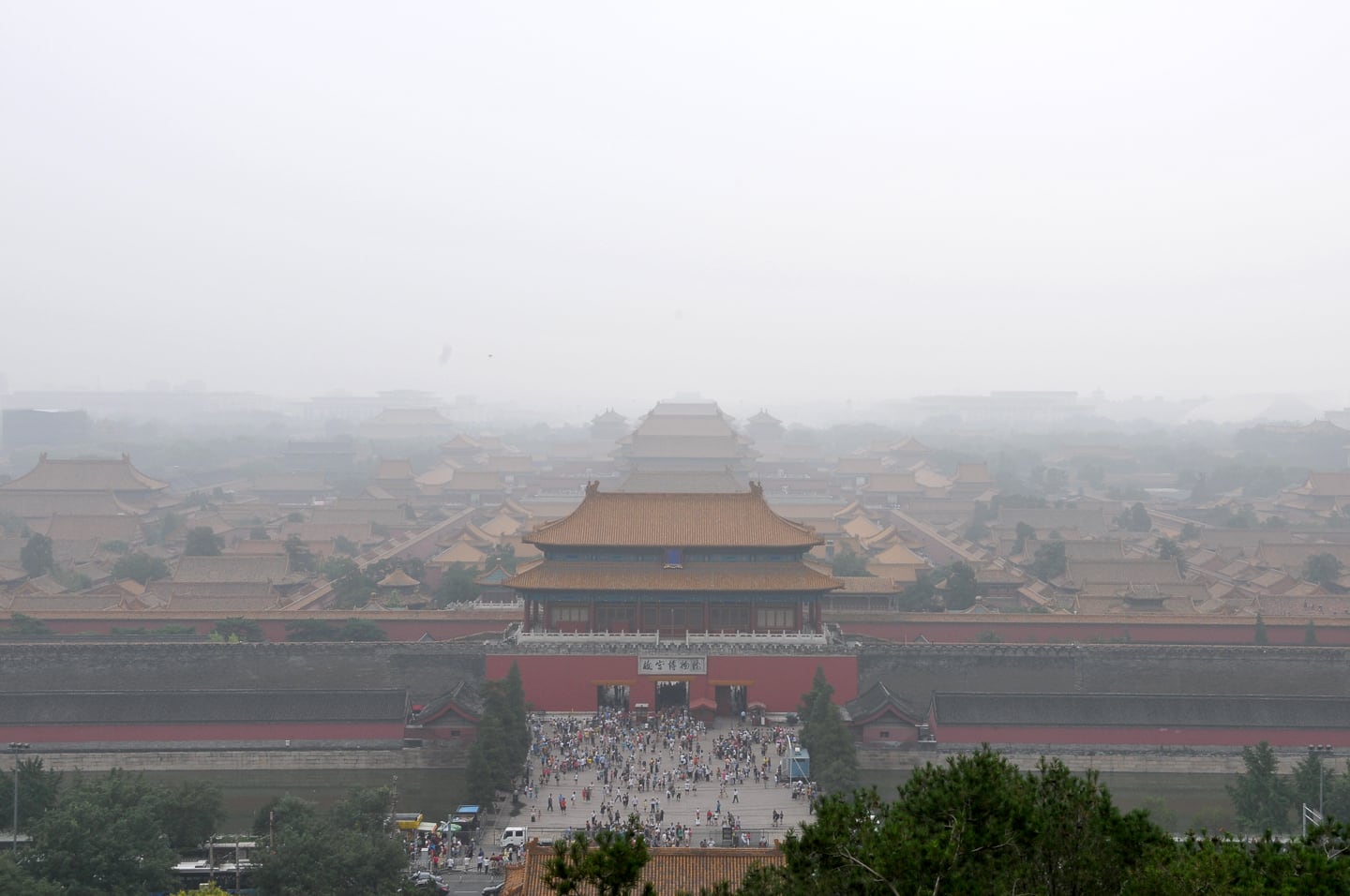

Out the north gate of the Forbidden City rises a large municipal park surrounding a towering hill on top of which sits an imposing pagoda. It’s a beautiful park laid out in classic Dynastic Chinese fashion (constructed long before the throws of Communism sucked the Fung Shue right out of public engineers and municipal architects).

The view from the top affords a magnificent panorama of the Forbidden City (and perhaps beyond if it weren’t for Beijing’s ever-present “fog”). Yet, the fog is a fitting accessary to the scene, given that a clear blue sky would seem jarringly out of place above the laid back and mysterious city of Beijing.

Olympic Sports Center

We very briefly toured the Olympic Sports Center, former home of the 2008 Summer Olympics. I say briefly because we arrived hungry, which is not the state you want to arrive at the Olympic Sports Center, for it is a virtual food desert. And like Tiananmen Square, it is a very hot, baren open space.

There are vendors which line the main thoroughfare, but they only sell water and various trinkets (our favorite was the Bird’s Nest glass ashtrays). We found one vendor which sold popcorn, but not a single place to have a proper meal of any kind.

The Bird’s Nest (National Stadium) was certainly the highlight of the short trip as it is an absolutely magnificent structure. Yet one can’t help but wonder what will become of the mammoth Olympic grounds. What will they do with all of the acres and acres of empty concrete space once the tourists stop coming? A good question, but one that the authorities won’t likely have to answer any time soon given that, to our surprise yet again, the Olympic grounds, even four years after its big event, still attracts Chinese tourists by the thousands.

Our absolute favorite thing to see and explore in Beijing were its famous hutongs (or alleyways), teeming with traditional urban life and excellent, inexpensive local restaurants.

One of our self-imposed missions led us through an especially confusing network of hutongs to a sealed metal door. I had read an article back in the states about China’s first craft brewery called Great Leap Brewing started by a master brewer from the U.S. I was especially excited to try the collection of brews he had created using local ingredients such as Sichuan peppers. Unfortunately, like so many websites in China, greatleapbrewing.com had apparently been a victim of the Great Firewall of China (we couldn’t access the site for all our efforts) and as a result had a heck of a time getting any information on the place. With address in hand (written in Chinese characters by helpful staff at our hostel), and a general idea of where it was, we set out to find it, and after much searching and finger-pointing were ultimately successful. If we had been able to access the website, we would have been able to learn that Great Leap Brewing was not open on this particular day, and tomorrow we would be on a train.

Got to leave some things for next time I suppose…

Speaking of catching a train out of Beijing, that was an entirely other wild goose chase story. We took our train to Pingyao (via Taiyuan) from Beijing West station, which is a massive Communist edifice topped by a decidedly out-of-place imperial-style pagoda. The station was the most ill-conceived, impractical train station I’ve ever been in, forcing travelers to climb several flights of stairs only to descend several flights of stairs and repeat the process over and over all in the name of forcing a train station into a structure design that should be nothing but a freestanding monument or memorial at best. I couldn’t help but marvel — as I peered at the virtually inaccessible monstrosity — at how fitting a metaphor it seemed for Communism in China: a massive ideological square peg constantly being forced into the round hole of human reality for which the Chinese populous continues to unabashedly bear the burden with each and every step.

I am heartened, however, to think of the magnificently well-designed ultra high-speed rail stations which have begun to emerge in most major cities that beautifully combine form with function with none of the Communist trappings of Beijing West and I can’t help but wonder if it is a sign of things to come. Certainly it is a sign of what is already happening today in China, something absolutely tangible if completely undefinable.

As always enjoyed your post so much!

Looking forward to the next one.

Much love, Grandma/ T.

Great pictures! Brought back lots of memories. Hutongs were our favorite too.. Sorry about the delibelly

Looking forward to more posts! Have fun! Be safe

Hugs Bill and Ann